Enabling effective outbreak management and public health emergency response

The theme for World Field Epidemiology Day 2022 (on 7 September) is Empowering Field Epidemiologists for Stronger Health Systems. As we wrote in an earlier blog, to celebrate, we are sharing weekly stories from Pacific field epidemiologists on the frontlines in our programs for each of the Day’s six sub-themes.

Today we are pleased to introduce you to Stanley Masi, a Field Epidemiology Training in Papua New Guinea (FETPNG) graduate, Advanced FETPNG fellow and District Health Program Manager for Wosera Gawi District in East Sepik Province. Stanley generously shares with us some of the frontline experience he has as a field epidemiologist in Papua New Guinea, speaking to the third sub-theme for World Field Epidemiology Day 2022: Enabling effective outbreak management and public health emergency response.

Stanley investigating a community’s water source during a dysentery outbreak

During the FETPNG Programs (both the intermediate and PNG’s advanced programs), I participated in two outbreaks in two different provinces, as well I participated in a number of health systems strengthening initiatives with measurable outcomes. I share about a selection of these here, and the field epidemiology skills I learned and applied in the field to enable effective outbreak management and public health emergency response.

The skills gained from FETPNG improved my performance, which was noted by the Senior Executive Management. As a result, they promoted me on the 5th August 2020 as the District Health Program Manager for Wosera Gawi District in East Sepik Province. My promotional position places me at a strategic location where I am able to make decisions to improve the health status of the people in the district and province as a whole.

I am proud to serve my people as a field epidemiologist on the frontline.

Stanley providing clinical support to a person with dysentery

Dysentery outbreak, 2018

On 16th January 2018, I was the team leader for a dysentery outbreak that claimed three lives in West Sepik Province. My team arrived in the outbreak site and held a meeting with a local health worker there to review his records to verify the outbreak. The records indicated that it was an outbreak. The next thing I did was meet with the communities and explain the reasons why we were there and what we were going to do. I held a meeting with the community and explain everything that they need to know about the disease and how to protect themselves from getting infected. After the meeting, communities brought in cases so my team and I interviewed and treated them following the national standard treatment protocol for dysentery in PNG. Very sick ones were brought to a constructed shelter for intensive management. Investigations were done and we clinically confirmed the outbreak.

I investigated the community’s toilet and several toilets were advised to be burnt down which the communities agreed as per my advice. New toilets were built. I also investigated the drinking and cooking water source high in the mountain and identified no visible substances relating to the outbreak as the water source is clean and originated underground. I was not able to test the water due to no testing equipment but communities were encouraged to boil water before they can drink. Stool samples were not collected due to walking distance as the plane only landed after every two to three weeks depending on when there is a charter for business houses or when the garden vegetable are ready and harvested to supply a nearby gold mine.

Immediate control measures implemented included home isolation of cases; only one person was appointed by immediate families to care for the patients while other families were restricted from coming in close contact with the cases until symptoms were subsided.

We stayed there for a week till no new cases were reported, then we left by walking for almost a week back to the health facility. After we arrived the local officer and communities communicated with me through the high frequency radio on weekly basis to update me on the control measures applied and how effective it was. They also called me to report if there were new cases. However, in this outbreak, no new cases were reported from the facility after my team left the village. The outbreak was contained without further transmission to the surrounding communities.

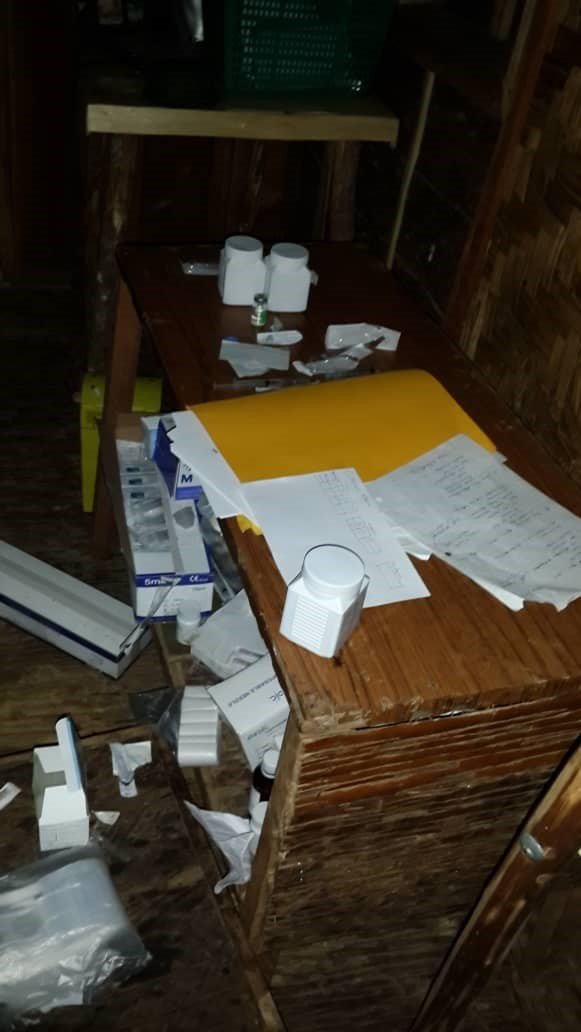

Here are some pictures of this outbreak investigation:

Pertussis outbreak, 2022

In May 2022 I led a team of other clinicians and communities to investigate a pertussis outbreak in East Sepik Province. We met with local health workers and confirmed the outbreak then we met with the primary school teachers, students and communities. We made known to them on our presence and what we were going to do. We gave health education on the subject as well.

On that same day students were reviewed and those who were clinically confirmed to have pertussis were treated and sent home with instructions on what to do while at home. We advised the students to tell their parents to come see us which they did. We did the active cases search into the village and identified a total of eighty cases which were interviewed, examined and were clinically confirmed to have pertussis. Samples were unable to be collected due to logistical challenges with testing.

All cases were treated using the national standard treatment guidelines for PNG. Other associated symptoms were treated symptomatically. Our team also vaccinated all the children who were due for their vaccines. A careful analysis into the outbreak revealed that most children from that village had not received their vaccines due to a month closure of the health facility and vaccine supply chain challenges. The findings are consistent as when there is a high immunity gap, outbreak is likely to occur. Parents were advised to do home isolation for their sick children. They were also advised not to allow their sick children to socialize with other children from the community for three weeks after their cough started. This control measures together with the clinical treatment and vaccination effectively controlled and contained the outbreak in that area.

Here are some photos of my investigation team and I transporting vaccines by cool box to the affected community.

Learning and applying outbreak skills, including community engagement principles

The skills learnt from FETPNG have helped me improve my performance in the organisation that I served. During the COVID-19 global pandemic I was part of the Surveillance and Emergency Response Team from the East Sepik Provincial Health Authority. Skills acquired greatly help me to make a case definition create line list, review persons of interest, interview contacts and do sample collection. Data management and data analysis were important part of the FETPNG training.

With the data management skills I learned in FETPNG, I was able to descriptively analyse case data by person, place and time. The skills helped me and my team to provide a timely report with public health interventions to the Senior Executive Management with a real-time evidence base for important decision making at the provincial level. Most of my recommended public health interventions were discussed and adopted by the Provincial Controller to assist him in writing out the East Sepik Provincial Control Measures during the COVID-19 global pandemic.

The principles of community engagement skills acquired in the FETPNG program have also worked well during the COVID-19 pandemic and other outbreak control measures. Principles such as clarifying or making known the purpose of the visit and any intervention to the community is very important in PNG society. Second thing is to understand the culture of the community; their perception, political, social, religious and their alliance with the outside community. Third thing is to establish a good working relationship with the community and leaders, both formal and informal to build a good trust between you and the community. Finally, is to carry out your intervention.

For instance, while conducting a COVID-19 vaccination campaign in a rural community, my team and I were approached by angry community members with machetes who were threatening us to leave. They believed many of the conspiracy theories that were around at the time, and thought that we, as healthcare workers, were bringing bad things to their people by bringing the vaccines. But we were bringing the vaccines to try to protect people’s lives! I worked with the community leaders to negotiate with these members, earning their trust. They then allowed us to stay.

I managed to hold several advocacy meetings with community leaders, community representatives both males and females, youth groups and other community-based groups. COVID-19 information was made available to them in simplified Melanesian Tok Pisin language. They were trained to identify symptomatic patients who have had travel to other places. They brought all suspected cases to the health facilities for testing and treatment. For those who were not able to bring the patients they contacted me through mobile phone before sending the patients. A small incentive was then budgeted for these community advocators so we pay them 20 kina ($8.33 AUD) per day. The leading district in terms of COVID-19 testing and vaccination was my district as a result of community engagement to health programs. Outbreak response skills was a very important part of the FETPNG training program.

Health systems strengthening

The country’s health system is assessed through the monthly reports from the National Health Information System (NHIS). I created a database where all monthly reports from the six reporting health facilities are submitted to the district health office by every 4th of the new month for analysis before they are being sent to the Provincial Health Information Office to be approved before sent to the NHIS office in Port Moresby. With the skills and knowledge acquired from the FETPNG program, I was able to analyse and interpret the data from the six health facilities and set interventions to improve each health programs in the district. I monitor and evaluate all health programs in the district against the PNGs 29 core health indicators to see if my district meets the target in every month or not. If the expected target is less then I give a call to the Officer in Charge (OIC) of the health facility or I visited the health facility to discuss and improve certain indicators. OICs are made aware of the 29 core health indicators that the PNGs health system is measured against. PNG Sector Performance Annual Report for last year (2021), my district – Wosera Gawi District – ranked first among other districts in East Sepik Province and ranked 25th out of 89 districts in PNG in certain indicators.

Outpatient attendance to other five health facilities were so high with limited workforce. After identifying that issue, I travelled to all the community aid posts to assess their status. I later realised that only one aid post was open for service in the district and that was the main contributing factor of high number of cases flooding the outpatient of the five health facilities.

I held an advocacy meeting with the community and stress on the importance of having an aid post nearby to ease the burden of walking long distance to access primary health care services. With the support from the East Sepik Provincial Health Authority and the communities, five new aid posts were reopened during the same year and are now actively providing services which reduces the case load encountered on daily basis by the other five reporting health facilities. The services provided by these five aid posts have greatly benefited the community and minimize preventable deaths.

Thank you, Stanley!

If you missed our first World Field Epidemiology Day sub-theme blog featuring John Landime sharing about his experience fighting outbreaks and health emergencies, including COVID-19, on the frontlines, or our second blog with Symphorian Sumun sharing about Strengthening surveillance systems to detect public health threats early, you can catch up here.

If you missed our first email newsletter, you can find it here and subscribe here to have all the feel-good field epi news delivered straight to your inbox each month!